Q.3: What are the various methods of obtaining knowledge? Give your own example of each method of learning. Also explain the distinguishing characteristics of scientific method of knowledge.

Various Methods of Obtaining Knowledge:

Introduction:

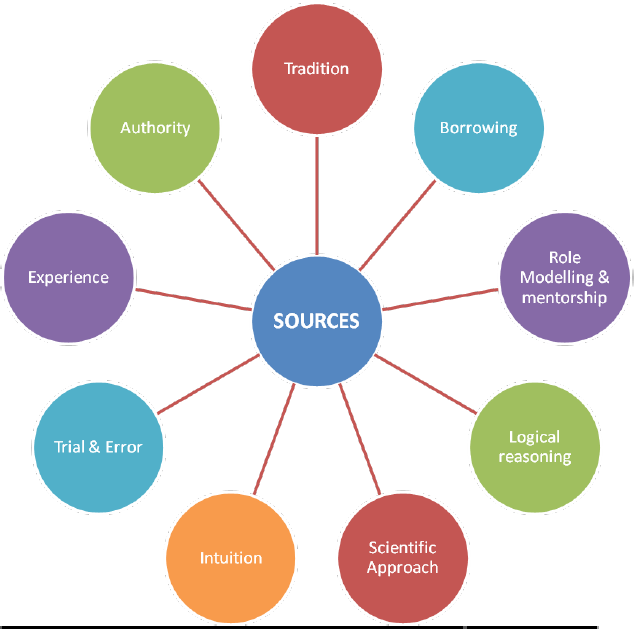

Knowledge is a complex, multifaceted concept. Information sources for clinical practice vary in dependability and validity. A brief discussion of some alternative sources of evidence shows how research based information is different. Nursing has historically acquired knowledge through traditions, authority, experience, borrowing, trial and error, role modeling and mentorship, intuition, reasoning and research.

Sources of Acquiring Knowledge:

NON-SCIENTIFIC WAYS OF OBTAINING KNOWLEDGE

1. COMMON SENSE: that which is self-evident

2. TENACITY: what we have known to be true in the past — holds firmly to beliefs because “it has always been so”.

3. AUTHORITY: established belief based on prominence or importance of source

4. INTUITION: something that just “stands to reason” — use of rational processes with benefit of experience

5. METAPHYSICS: investigates principles of reality

(visible and invisible), the essence of things. Construct theories on the basis of a priori knowledge, that is, knowledge derived from reason alone.

6. RA TIONALISM: criterion of truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive.

7. EMPIRICISM: relying on the “observable”; through one’s own experience

SCIENTIFIC METHOD

Research Methods in the Social Sciences

• The social sciences have adopted the scientific method as a way of “knowing”

– Empirical (rather than normative)

– Objective (rather than subjective)

– Systematic (rather than random)

– Rigorous (meticulous, painstaking)

This method has evolved from a very long debate about truth and knowledge.

• Socrates (469-399 BCE): “I know that I know nothing”

• Aresilaus (314-241 BCE) said he was not even certain that he was uncertain.

• Carneades (213-128 BCE) knowledge and truth is impossible.

• Sextus Empiricus (CE 200) science based on reason or logic is not to be trusted. Experiences is our best guide.

• Pyrrho (365-275 BCE): one must neither trust nor reject your senses.

For many centuries, intellectuals who were interested in knowledge hoped that if scientific inquiry could become sufficiently empirical, it could be our best guide to certitude or, at least, probability.

From these early thinkers came the early modern effort to establish an empirical “scientific method.” This way of thinking had great influence on the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

Scientific Revolution (16th & 17th Century)

• For example Galileo argued explicitly against traditional Greek traditions and against the principle of intellectual authority. Facts are determined by nature, not by books or men-not even the pope.

• The authors of this time, rejecting authority, believed that for the first time, with proper method, the human mind was looking on God’s work with understanding.

Francis Bacon (1561-1621)

– Natural philosophy (science) must be separated from theology

– The method of induction, from particular to the general, is tested by experiment

-Science is a dynamic, cooperative, cumulative enterprise.

– Science is always self-correcting

Science and the Scientific Method

• This class, and much of our field, assumes that the scientific method is the best method for answering questions in the physical, social, and political world.

• Not everyone is convinced that the scientific method is obtainable or appropriate, but before you reject the approach you must first master it.

Why is a scientific approach better?

Even as far back as the pre-Socratics (6th/5th centuries BCE) like the Milesian physicists, who rejected the supernatural and religious explanations, scholars have argued for a more naturalistic and scientific approach.

COMMON ERRORS IN HUMAN INQUIRY

1. INACCURATE OBSERVATION

2. OVERGENERALIZATION

3. SELECTIVE OBSERVATION

4. MADE-UP INFORMATION

5. ILLOGICAL REASONING

6. EGO-INVOLVEMENT IN UNDERSTANDING

7. PREMATURE CLOSURE OF INQUIRY

8. MYSTIFICATION OF RESIDUALS

Does the scientific method correct for these common errors in human inquiry?

Yes and no. A systematic, rigorous, empirical, approach can help avoid such problems, especially if such an approach is embedded in a philosophy of skepticism that requires replication and verification.

But humans are the ones that conduct science and because humans are imperfect, the application of the methods may be imperfect

SOURCES OF ERROR IN RESEARCH

A. CENTER OF ATTENTION EFFECTS

1. Hawthorne Effect — The effect of being studied and reacting favorably to the study. The term comes from a series of experiments on factory workers in the 1920s. The purpose was to find the optimum level of lighting for productivity.

• Study 1: no control group. The researchers experimented on three different departments; all showed an increase of productivity, whether illumination increased or decreased.

• Study 2: A control group had no change in lighting, while the experimental group got a sequence of increasing light levels. Both groups substantially increased production, and there was no difference between the groups.

• Study 3: The researchers decided to see what would happen if they decreased lighting. The control group got stable illumination; the other got a sequence of decreasing levels. Surprisingly, both groups steadily increased production until finally the light in experimental group got so low that they protested and production fell off.

• Study 4: This was conducted on two women only. Their production stayed constant under widely varying light levels. It was found that if the experimenter said bright was good, they said they preferred the light; the same was true when he said dimmer was good.

• At this point, researchers realized that something else besides lighting was affecting productivity. They suspected that the supervision of the researchers had some effect, so they ended the illumination experiments in 1927.

B. SAMPLING AND SUBJECT SELECTION

1. Sample size and sampling frame — number of cases, random selection, representativeness (Dewey Defeats Truman; Landon in a Landslide)

2. Mortality — loss of subjects during the course of the research (School Choice)

ASSUMPTIONS OF SCIENCE

1. Systematic Investigation

2. Deterministic

3. Empirical/observable

4. Measurable

5. Ongoing

6. Skeptical

7. Public

8. Value-free

9. Logical

10. Probabilistic reasoning

Do these assumptions hold?

A. VALUE FREE?

personal values/interests interpretation of results funding agencies

B. PRACTICAL ISSUES: Time, Money, Situation

C. ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

voluntary participation confidentiality/anonymity concealment of research identity

D. POLITICAL CONSIDERATIONS

objectivity and ideology

effect of research on legislation, spending,

creation of programs

Critics of the Scientific Method

Post-positivists

• Objectivity is impossible

• Observations are skewed by your perceptions

• Knowledge is still often based on authority

• Subjectivity and values are not necessarily a bad thing

Course Objectives:

• Understand the purpose and process of the scientific method.

• Obtain a familiarity with a variety of research designs and methodologies.

• Obtain a familiarity with statistical analysis of data

• Prepare a research design for a future project (i.e., a MA thesis)