Dependency theory emerged in Latin America in the late 1960s and 1970s, partly as a consequence of the political situation in the continent, with increasing US support for right-wing authoritarian governments, and partly with the realization among the educated elite that the developmentalist approach to international communication had failed to deliver. The establishment, in 1976, in Mexico City of the Instituto Latinamericano de Estudios (ILET), whose principal research interest was the study of transnational media business, gave an impetus to a critique of the ‘modernization’ thesis, documenting its negative consequences in the continent. The impact of ILET was also evident in international policy debates about NWICO, particularly through the work of Juan Somavia, a member of the MacBride Commission.

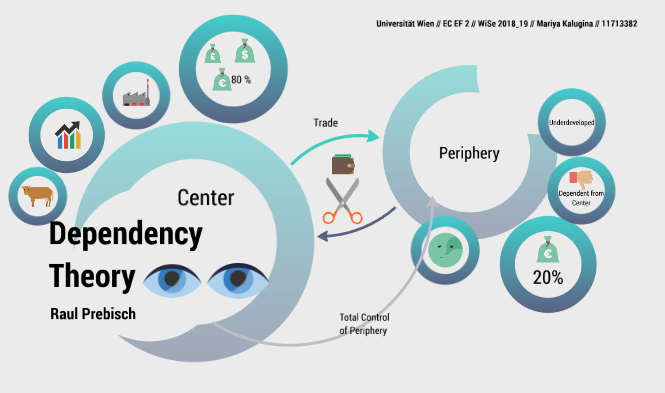

Though grounded in the neo-Marxist political-economy approach (Baran, 1957; Gunder Frank, 1969; Amin 1976), dependency theorists aimed to provide an alternative framework to analyse international communication. Central to dependency theory was the view that transnational corporations (TNCs), most based in the North, exercise control, with the support of their respective governments, over the developing countries by setting the terms for global trade – dominating markets, resources, production, and labour. Development for these countries was shaped in a way to strengthen the dominance of the developed nations and to maintain the ‘peripheral’ nations in a position of dependence – in other words, to make conditions suitable for ‘dependent development’. In its most extreme form the outcome of such relationship was ‘the development of underdevelopment’ (Gunder Frank, 1969).

This neo-colonial relationship in which the TNCs controlled both the terms of exchange and the structure of global markets, it was argued, had contributed to the widening and deepening of inequality in the South while the TNCs had strengthened their control over the world’s natural and human resources (Baran, 1957; Mattelart, 1979).

The cultural aspects of dependency theory, examined by scholars interested in the production, distribution and consumption of media and cultural products, were particularly relevant to the study of international communication. The dependency theorists aimed to show the links between discourses of ‘modernization’ and the policies of transnational media and communication corporations and their backers among Western governments.

Dependency theorists both benefited from, and contributed to, research on cultural aspects of imperialism being undertaken at the time in the USA. The idea of cultural imperialism is most clearly identified with the work of Herbert Schiller, who was based at the University of California (1969/92).Working within the neo-Marxist critical tradition, Schiller analysed the global power structures in the international communication industries and the links between transnational business and the dominant states.

At the heart of Schiller’s argument was the analysis of how, in pursuit of commercial interests, huge US-based transnational corporations, often in league with Western (predominantly US) military and political interests, were undermining the cultural autonomy of the countries of the South and creating a dependency on both the hardware and software of communication and media in the developing countries. Schiller defined cultural imperialism as:

the sum of the processes by which a society is brought into the modern world system and how its dominating stratum is attracted, pressured, forced, and sometimes bribed into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even to promote, the values and structures of the dominant centre of the system. (Schiller, 1976: 9)

Schiller argued that the declining European colonial empires – mainly British, French and Dutch – were being replaced by a new emergent American empire, based on US economic, military and informational power.

According to Schiller, the US-based TNCs have continued to grow and dominate the global economy. This economic growth has been underpinned with communications know-how, enabling US business and military organizations to take leading roles in the development and control of new electronically- based global communication systems.

Such domination had both military and cultural implications. Schiller’s seminal work, Mass Communications and American Empire (1969/1992), examined the role of the US government, a major user of communication services, in developing global electronic media systems, initially for military purposes to counter the perceived, and often exaggerated, Soviet security threat. By controlling global satellite communications, the USA had the most effective surveillance system in operation – a crucial element in the Cold War years. Such communication hardware could also be used to propagate the US model of commercial broadcasting, dominated by large networks and funded primarily by advertising revenue. Nothing less than the viability of the American industrial economy itself is involved in the movement toward international commercialisation of broadcasting. The private yet managed economy depends on advertising. Remove the excitation and the manipulation of consumer demand and industrial slowdown threatens. (Schiller, 1969: 95)

According to Schiller, dependence on US communications technology and investment, coupled with the new demand for media products, necessitated large-scale imports of US media products, notably television programmes. Since media exports are ultimately dependent on sponsors for advertising, they endeavour not only to advertise Western goods and services, but also promote, albeit indirectly, a capitalist ‘American way of life’, through mediated consumer lifestyles. The result was an ‘electronic invasion’, especially in the global South, which threatened to undermine traditional cultures and emphasize consumerism at the expense of community values.

US dominance of global communication increased during the 1990s with the end of the Cold War and the failure of the UNESCO-supported demands for NWICO, Schiller argued in the 1992 revised edition of the book. The economic basis of US dominance, however, had changed, with TNCs acquiring an increasingly important role in international relations, transforming US cultural imperialism into ‘transnational corporate cultural domination’ (Schiller, 1992: 39).

In a recent review of the US role in international communication during the past half-century, Schiller saw the US state still playing a decisive role in promoting the ever-expanding communication sector, a central pillar of the US economy. In US support for the promotion of electronic-based media and communication hardware and software in the new information age of the twenty-first century, Schiller found ‘historical continuities in its quest for systemic power and control,’ of global communication (1998: 23).

Other prominent works employing what has come to be known as ‘the cultural imperialism thesis’ have examined such diverse aspects of US cultural and media dominance as Hollywood’s relationship with the European movie market (Guback, 1969); US television exports and influences in Latin America (Wells, 1972); the contribution of Disney comics in promoting capitalist values (Dorfman and Mattelart, 1975) and the role of the advertising industry as an ideological instrument (Ewen, 1976; Mattelart, 1991). Internationally, some of the most significant work has been the UNESCOsupported research on international flow in television programmes (Nordenstreng and Varis, 1974; Varis, 1985).

One prominent aspect of dependency in international communication was identified in the 1970s by Oliver Boyd-Barrett as ‘media imperialism’, examining information and media inequalities between nations and how these reflect broader issues of dependency, and analysing the hegemonic power of mainly US-dominated international media – notably news agencies, magazines, films, radio and television. Boyd-Barrett defined media imperialism as:

The process whereby the ownership, structure, distribution or content of the media in any one country are singly or together subject to substantial external pressures from the media interests of any other country or countries, without proportionate reciprocation of influence by the country so affected. (1977:117)

For its critics, dependency literature was ‘notable for an absence of clear definitions of fundamental terms like imperialism and an almost total lack of empirical evidence to support the arguments’ (Stevenson, 1988: 38). Others argued that it ignored the question of media form and content as well as the role of the audience. Those involved in a cultural studies approach to the analysis of international communication argued that, like other cultural artefacts, media ‘texts’ could be polysemic and were amenable to different interpretations by audiences who were not merely passive consumers but ‘active’ participants in the process of negotiating meaning (Fiske, 1987). It was also pointed out that the ‘totalistic’ cultural imperialism thesis did not adequately take on board such issues as how global media texts worked in national contexts, ignoring local patterns of media consumption.

Quantifying the volume of US cultural products distributed around the world was not a sufficient explanation, it was also important to examine its effects. There was also a view that cultural imperialism thesis assumed a ‘hypodermic-needle model’ of media effects and ignored the complexities of ‘Third World’ cultures (Sreberny-Mohammadi, 1991; 1997). It was argued that the Western scholars had a less than deep understanding of Third World cultures, seeing them as homogeneous and not being adequately aware of the regional and intra-national diversities of race, ethnicity, language, gender and class. However, there have yet been few systematic studies of the cultural and ideological effects of Western media products on audiences in the South, especially from Southern scholars.

Despite its share of criticism (Tomlinson, 1991; Thompson, 1995), the cultural imperialism thesis was very influential in international communication research in the 1970s and 1980s. It was particularly important during the heated NWICO debates in UNESCO and other international fora in the 1970s. However, even a critic such as John Thompson, while rejecting the main thesis, has conceded that such research is ‘probably the only systematic and moderately plausible attempt to think about the globalisation of communications and its impact on the modern world’ (Thompson, 1995: 173).

Defenders of the thesis found the 1990s’ debates criticizing cultural imperialism ‘lacking even the most elementary epistemological precaution and sometimes actually bordering on intellectual dishonesty’, arguing that the critics of this theory have often ‘taken the notion out of context, abstracting it from the concrete historical conditions that produced it: the political struggles and commitments of the 1960s and 1970s’ (Mattelart and Mattelart, 1998: 137-8).

With changes in debates on international communication reflecting the rhetoric of privatization and liberalization in the 1990s, theories of media and cultural dependency have become less prominent. However, Boyd- Barrett has argued that while media imperialism theory, in its original formulation, did not take into account intra-national media relations, gender and ethnic issues, it is still a useful analytical tool to make sense of what he terms as the ‘colonisation of communications space’ (Boyd- Barrett, 1998: 157).

One of the limits of the cultural and media imperialism approach is that it did not fully take into account the role of the national elites, especially in the developing world. However, though its influence has dwindled, the theory of structural imperialism developed by the Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung, also offers an explanation of the role of international communication in maintaining structures of economic and political power.