MEDIA AND CULTURE THEORIES: MEANING-MAKING IN THE SOCIAL WORLD

Symbolic Interactionism

Symbolic Interactionism Theory that people give meaning to symbols and that those meanings come to control those people

Social Behaviorism View of learning that focuses on the mental processes and the social environment in which learning takes place

Symbolic interactionism was one of the first social science theories to address questions of how communication is involved with the way we learn culture and how culture structures our everyday experience. Symbolic interaction theory developed during the 1920s and 1930s as a reaction to and criticism of behaviorism, and it had a variety of labels until Herbert Blumer gave it its current name in 1969. One early name was social behaviorism. Unlike traditional behaviorists, social behaviorists rejected simplistic conceptualizations of stimulus response conditioning. They were convinced that attention must be given to the cognitive processes mediating learning. They also believed that the social environment in which learning takes place must be considered. Traditional behaviorists tended to conduct laboratory experiments in which animals were exposed to certain stimuli and conditioned to behave in specific ways. Social behaviorists judged these experiments too simplistic. They argued that human existence was far too complex to be understood through conditioning of animal behavior.

PRAGMATISM AND THE CHICAGO SCHOOL

Symbols In general, arbitrary, often abstract representations of unseen phenomena

Mead developed symbolic interactionism by drawing on ideas from pragmatism, a philosophical school of theory emphasizing the practical function of knowledge as an instrument for adapting to reality and controlling it. Pragmatism developed in America as a reaction against ideas gaining popularity at home and in Europe at the end of the nineteenth century—simplistic forms of materialism such as behaviorism and German idealism. Both behaviorism and idealism rejected the possibility of human agency: that individual could consciously control their thoughts and actions in some meaningful and useful way. Idealism argued that people are dominated by culture, and behaviorism argued that all human action is a conditioned response to external stimuli. From the preceding description of Mead’s ideas, you can see how he tried to find a middle ground between these two perspectives—a place that would allow for some degree of human agency. If we consider Mead’s arguments carefully, they allow for individuals to have some control over what they do, but he is really arguing that agency lies with the community. Communities create and propagate culture: the complex sets of symbols that guide and shape our experiences. When we act in communities, we are mutually conditioned so we learn culture and use it to structure experience.

For pragmatists, the basic test of the power of culture is the extent to which it effectively structures experience within a community. When some aspect of culture loses its effectiveness, it ceases to structure experience and becomes a set of words and symbols having essentially no meaning.

Current Applications of Symbolic Interactionism

Although Mead first articulated his ideas in the 1930s, it was not until the 1970s and 1980s those mass communication researchers gave serious attention to symbolic interaction. Given the great emphasis that Mead placed on interpersonal interaction and his disregard for media, it is not surprising that media theorists were slow to see the relevancy of his ideas. Michael Solomon (1983), a consumer researcher, provided a summary of Mead’s work that is especially relevant for media research:

- Cultural symbols are learned through interaction and then mediate that interaction.

- The “overlap of shared meaning” by people in a culture means that individuals who learn a culture should be able to predict the behaviors of others in that culture.

- Self-definition is social in nature; the self is defined largely through interaction with the environment.

- The extent to which a person is committed to a social identity will determine the power of that identity to influence his or her behavior.

Symbolic Interactionism

| Strengths | Weakness |

| 1. Rejects simple stimulus-response conceptualizations of human behavior2. Considers the social environment in which learning takes place

3. Recognizes the complexity of human existence 4. Foregrounds individuals’ and the community’s role in agency 5. Provides basis for many methodologies and approaches to inquiry |

1. Gives too little recognition to power of social institutions2. In some contemporary articulations, grants too much power to media content |

Social Constructionism

Social Constructionism School of social theory that argues that individuals’ power to oppose or reconstruct important social institutions is limited

Social Construction of reality Theory that assumes an ongoing correspondence of meaning because people share a common sense about its reality

Phenomenology Theory developed by European philosophers focusing on individual experience of the physical and social world

Typifications “Mental images” that enable people to quickly classify objects and actions and then structure their own actions in response

| Strengths | Weakness |

| 1. Rejects simple stimulus-response conceptualizations of human behavior2. Considers the social environment in which learning takes place

3. Recognizes the complexity of human existence 4. Foregrounds social institutions’ role in agency 5. Provides basis for many methodologies and approaches to inquiry |

1. Gives too little recognition to power of individuals and communities2. In some contemporary articulations, grants too much power to media content |

Framing and Frame Analysis

Frame Analysis Goffman’s idea about how people use expectations to make sense of everyday life

While critical cultural researchers were developing reception analysis during the 1980s, a new approach to audience research was taking shape in the United States. It had its roots in symbolic interaction and social constructionism. As we’ve seen, both argue that the expectations we form about ourselves, other people, and our social world are central to social life. You have probably encountered many terms in this and other textbooks that refer to such expectations—stereotypes, attitudes, typification schemes, and racial or ethnic bias. All these concepts assume that our expectations are socially constructed:

- Expectations are based on previous experience of some kind, whether derived from a media message or direct personal experience (in other words, we aren’t born with them).

- Expectations can be quite resistant to change, even when they are contradicted by readily available factual information.

- Expectations are often associated with and can arouse strong emotions such as hate, fear, or love.

- Expectations often get applied by us without our conscious awareness, especially when strong emotions are aroused that interfere with our ability to consciously interpret new information available in the situation.

Social Cues In frame analysis, information in the environment that signals a shift or change of action

Frame In frame analysis, a specific set of expectations used to make sense of a social situation at a given point in time

Downshift and Upshift In frame analysis, to move back and forth between serious and less serious frames

Hyperritualized representations Media content constructed to highlight only the most meaningful actions

Primary, or dominant, reality In frame analysis, the real world in which people and events obey certain conventional and widely accepted rules (sometimes referred to as the dominant reality)

| Strengths | Weakness |

| 1. Focuses attention on individuals in the mass communication process2. Micro-level theory but is easily applicable to macro-level effects issues

3. Is highly flexible and open-ended 4. Is consistent with recent findings in cognitive psychology |

1. Is highly flexible and open-ended (lacks specificity)2. Is not able to address presence or absence of effects

3. Precludes causal explanations because of qualitative research methods 4. Assumes individuals make frequent framing errors; questions individuals’ abilities |

Recent Theories of Frames and Framing

A conceptual framework that considers (1) the social and political context in which framing takes place, and (2) the long-term social and political consequences of media-learned frames. Most of this framing research has focused on journalism and on the way news influences our experience of the social world. Early examples of framing research applied to journalism can be found in the scholarship of two sociologists whom you met in the last chapter, Todd Gitlin (1980) and Gaye Tuchman (1978). Their work is frequently cited and played an important role in extending Goffman’s ideas. Gitlin focused on news coverage of politically radical groups during the late 1960s. He argued that they were systematically presented in ways that demeaned their activities and ignored their ideas. These representations made it impossible for them to achieve their objectives. Tuchman focused on routine news production work and the serious limitations inherent in specific strategies for coverage of events. Although the intent of these practices is to provide objective news coverage, the result is news stories in which events are routinely framed in ways that eliminate much of their ambiguity and instead reinforce socially accepted and expected ways of seeing the social world.

Framing and Objectivity

Framing theory challenges a long accepted and cherished tenet of journalism—the notion that news stories can or should be objective. Instead, it implies that journalism’s role should be to provide a forum in which ideas about the social world are routinely presented and debated. As it is now, this forum is dominated by social institutions having the power to influence frames routinely used to structure news coverage of the social world.

News Reality Frames News accounts in which interested elites involve journalists in the construction of news drama that blurs underlying contextual realities

Effects of Frames on News Audiences

Researchers have documented the influence frames can have on news audiences. The most common finding is that exposure to news coverage results in learning that is consistent with the frames that structure the coverage. If the coverage is dominated by a single frame, especially one originating from an elite source, learning will tend to be guided by this frame (Ryan, Carragee, and Meinhofer, 2001; Valkenburg and Semetko, 1999). What this research has also shown is that news coverage can strongly influence the way news readers or viewers make sense of news events and their major actors. This is especially true of news involving an ongoing series of highly publicized and relevant events, such as social movements (McLeod and Detenber, 1999; Nelson and Clawson, 1997; Terkildsen and Schnell, 1997). Typically, news coverage is framed to support the status quo, resulting in unfavorable views of movements. The credibility and motives of movement leaders are frequently undermined by frames that depict them as overly emotional, disorganized, or childish.

Reforming Journalism Based on Framing Theory

Some framing theorists have begun to advocate changes in journalism that might overcome these limitations. Gans (2003) advocates what he calls participatory news. This is news that reports how citizens routinely engage in actions that have importance for their communities. He points out that this type of coverage has vanished even from local newspapers, but it could be a vital part of encouraging more people to become politically engaged. Participatory news could range from covering conversations in coffee shops to reports on involvement in social groups. Reports on social movements could be “reframed” so they feature positive aspects rather than threats posed to the status quo. He argues that coverage of participation is the best way for journalists to effectively promote it.

Participatory News News that reports how citizens routinely engage in actions that have importance for their communities

Explanatory journalism News that answers “why” questions

Collective Action Frames News frames highlighting positive aspects of social movements and the need for and desirability of action

Cultivation Analysis

Cultivation Analysis Theory that television “cultivates” or creates a worldview that, although possibly inaccurate, becomes the reality because people believe it to be so

You can begin your own evaluation of cultivation analysis by answering three questions:

- In any given week, what are the chances that you will be involved in some kind of violence: about 1 in 10 or about 1 in 100? In the actual world, about 0.41 violent crimes occur per 100 Americans, or less than 1 in 200. In the world of prime-time television, though, more than 64 percent of all characters are involved in violence. Was your answer closer to the actual or to the television world?

- What percentage of all working males in the United States toil in law enforcement and crime detection: 1 percent or 5 percent? The U.S. Census says 1 percent; television says 12 percent. What did you say?

- Of all the crimes that occur in the United States in any year, what proportion is violent crime, like murder, rape, robbery, and assault? Would you guess 15 or 25 percent? If you hold the television view, you chose the higher number. On television, 77 percent of all major characters who commit crimes commit the violent kind. The Statistical Abstract of the United States reports that in actuality only 10 percent of all crime in the country is violent crime.

Violence Index Annual content analysis of a sample week of network television prime-time fare demonstrating how much violence is present

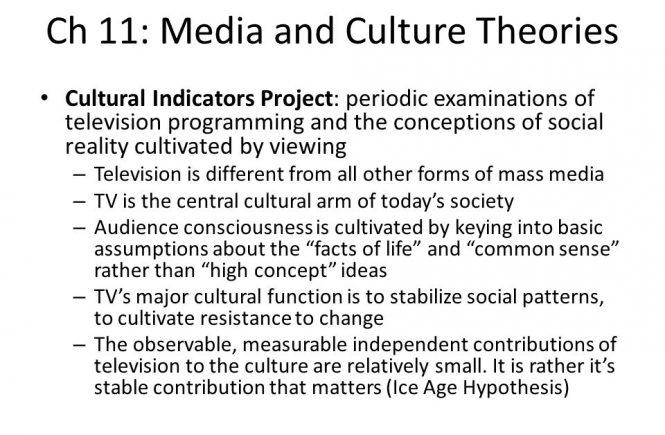

Cultural Indicators Project In cultivation analysis, periodic examinations of television programming and the conceptions of social reality cultivated by viewing

The Products of Cultivation Analysis

To scientifically demonstrate their view of television as a culturally influential medium, cultivation researchers depended on a four-step process. The first they called message system analysis, detailed content analyses of television programming to assess its most recurring and consistent presentations of images, themes, values, and portrayals. The second step is the formulation of questions about viewers’ social realities. Remember the earlier questions about crime? Those were drawn from a cultivation study. The third step is to survey the audience, posing the questions from step two to its members and asking them about their amount of television consumption. Finally, step four entails comparing the social realities of light and heavy viewers. The product, as described by Michael Morgan and Nancy Signorielli, should not be surprising: “The questions posed to respondents do not mention television, and the respondents’ awareness of the source of their information is seen as irrelevant. The resulting relationships … between amount of viewing and the tendency to respond to these questions in the terms of the dominant and repetitive facts, values, and ideologies of the world of television … illuminate television’s contribution to viewers’ conceptions of social reality” (2003, p. 99).

The Mean World Index

Some of the most interesting and important issues for cultivation analysis involve the symbolic transformation of message system data into more general issues and assumptions” (Morgan, Shanahan, and Signorielli, 2009, p. 39). As an example, cultivation researchers present the Mean World Index, a series of three questions:

- Do you believe that most people are just looking out for themselves?

- Do you think that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?

- Do you think that most people would take advantage of you if they got the chance?

Media as Culture Industries: The Commodification of Culture

One of the most intriguing and challenging perspectives to emerge from critical cultural studies is the commodification of culture, the study of what happens when culture is mass-produced and distributed in direct competition with locally based cultures (Enzensberger, 1974; Hay, 1989; Jhally, 1987). According to this viewpoint, media are industries specializing in the production and distribution of cultural commodities. As with other modern industries, they have grown at the expense of small local producers, and the consequences of this displacement have been and continue to be disruptive to people’s lives.

In earlier social orders, such as medieval kingdoms, the culture of everyday life was created and controlled by geographically and socially isolated communities. Though kings and lords might dominate an overall social order and have their own culture, it was often totally separate from and had relatively little influence over the folk cultures structuring the everyday experience of average people. Only in modern social orders have elites begun to develop subversive forms of mass culture capable of intruding into and disrupting the culture of everyday life, argue commodification-of-culture theorists. These new forms function as very subtle but effective ways of thinking, leading people to misinterpret their experiences and act against their own self-interests.

Commodification of culture The study of what happens when culture is mass produced and distributed in direct competition with locally based cultures

| Strengths | Weakness |

| 1. Provides basis for social change2. Identifies problems created by repackaging of cultural content | 1. Argues for, but does not empirically demonstrate, effects2. Has overly pessimistic view of media influence and average people |

Advertising: The Ultimate Cultural Commodity

Advertising packages promotional messages so they will be attended to and acted on by people who often have little interest in and often no real need for most of the advertised products or services. Marketers routinely portray consumption of specific products as the best way to construct a worthwhile personal identity, have fun, make friends and influence people, or solve problems (often ones we never knew we had). You deserve a break today. Just do it. DewMocracy!

Compared to other forms of mass media content, advertising comes closest to fitting older Marxist notions of ideology. It is intended to encourage consumption that serves the interest of product manufacturers but may not be in the interest of individual consumers.

The Media Literacy Movement

Media Literacy The ability to access, analyzes, evaluate, and communicate messages

The media literacy movement is based on insights derived from many different sources. We list some of the most important here:

- Audience members are indeed active, but they are not necessarily very aware of what they do with media (uses and gratifications).

- The audience’s needs, opportunities, and choices are constrained by access to media and media content (critical cultural studies).

- Media content can implicitly and explicitly provide a guide for action (social cognitive theory, social semiotic theory, symbolic interaction, social construction of reality, cultivation, framing).

- People must realistically assess how their interaction with media texts can determine the purposes that interaction can serve for them in their environments (cultural theory).

- People have differing levels of cognitive processing ability, and this can radically affect how they use media and what they are able to get from media (information-processing theory).

Two Views of Media Literacy

Mass communication scholar Art Silverblatt provided one of the first systematic efforts to place media literacy in audience- and culture-centered theory and frame it as a skill that must and can be improved. His core argument parallels a point made earlier: “The traditional definition of literacy applies only to print: ‘having a knowledge of letters; instructed; learned.’ However, the principal channels of media now include print, photography, film, radio, and television. In light of the emergence of these other channels of mass communications, this definition of literacy must be expanded” (1995, pp. 1–2). As such, he identified five elements of media literacy:

- An awareness of the impact of the media on the individual and society

- An understanding of the process of mass communication

- The development of strategies with which to analyze and discuss media messages

- An awareness of media content as a “text” that provides insight into our contemporary culture and ourselves

- The cultivation of an enhanced enjoyment, understanding, and appreciation of media content

Potter (1998) takes a slightly different approach, describing several foundational or bedrock ideas supporting media literacy:

- Media literacy is a continuum, not a category. “Media literacy is not a categorical condition like being a high school graduate or being an American…. Media literacy is best regarded as a continuum in which there are degrees…. There is always room for improvement”.

- Media literacy needs to be developed. “As we reach higher levels of maturation intellectually, emotionally, and morally we are able to perceive more in media messages…. Maturation raises our potential, but we must actively develop our skills and knowledge structures in order to deliver on that potential” .

- Media literacy is multidimensional. Potter identifies four dimensions of media literacy. Each operates on a continuum. In other words, we interact with media messages in four ways, and we do so with varying levels of awareness and skill:

- The cognitive domain refers to mental processes and thinking.

- The emotional domain is the dimension of feeling.